Refine search

No keyword found to refine search

keywords EN

Places

Names

174 documents found

| 1 | 3 |

Documents per page :

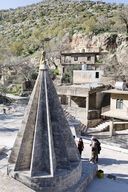

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282186.jpg

View of the Lalish temples.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

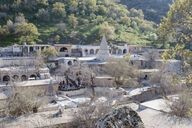

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282187.jpg

View of the Lalish temples.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282188.jpg

View of the Lalish temples.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282189.jpg

View of the Lalish temples.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282190.jpg

View of the Lalish temples.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282191.jpg

The faithful rest during a pilgrimage.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282192.jpg

Pilgrims in Lalish.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282193.jpg

View of the Lalish temples.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282194.jpg

View of the Lalish temples.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282195.jpg

View of the Lalish temples.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282196.jpg

The main street of the Lalish religious complex.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282197.jpg

Pilgrims in Lalish.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282198.jpg

A priestess during a ceremony in Lalish.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282199.jpg

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282200.jpg

A pilgrim kisses a sacred stone in Lalish.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

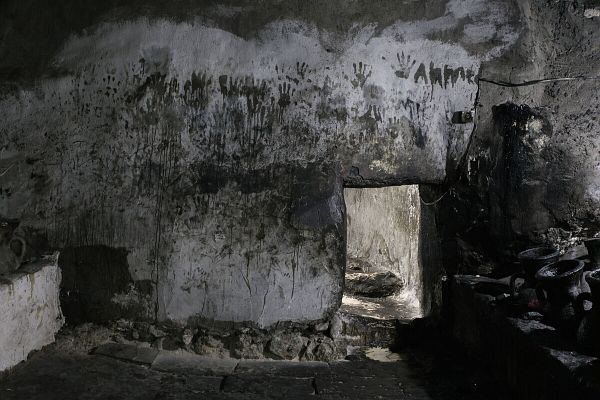

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282201.jpg

The Hesen Dana room, containing the jars filled with the oil used to light the temple's 365 lamps.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282202.jpg

The Hesen Dana room, containing the jars filled with the oil used to light the temple's 365 lamps.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282203.jpg

A group of Yezidi men in the temple's central courtyard.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish

Gabriel Gauffre / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0282204.jpg

The tomb of Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Lalish, located in the heart of Iraqi Kurdistan, is the most sacred site to the Yazidi. They must make the pilgrimage there at least once in their life, for six days, in order to pay their respects to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir’s tomb, the founder of the religion. They are about 700 000 in Iraq. Founded in the 12th century, the religion mixes elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs, making them a major target during the expansion of the Islamic state in Iraq.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234798.jpg

Portrait of Bernadette in one of the halls of a building where the sick sleep. Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234799.jpg

Pilgrims drink water from shells at the new fountains of the sanctuary. Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234800.jpg

Pilgrims drink water from shells at the new fountains of the sanctuary. Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234801.jpg

Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234802.jpg

People seated in wheelchairs. Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234803.jpg

Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234804.jpg

hospitable in white. Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234805.jpg

Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234806.jpg

Pilgrims in wheelchairs in the grotto of Lourdes. Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234807.jpg

torchlight procession. Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234808.jpg

torchlight procession. Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

Pilgrimage to Lourdes

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0234809.jpg

torchlight procession. Pilgrimage of Aveyronnaise Hospitality to Lourdes. Hospital workers are people present to take care of sick and / or elderly people. They thus allow them to live their faith like everyone else. Carts are available to move people quickly and easily. August 2018. Lourdes, France.

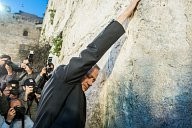

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217656.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, touches the stones of the Western Wall in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019, as he campaigns ahead of the parliamentary polls scheduled for April 9.

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217657.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, visits the Western Wall Tunnels in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019.

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217658.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, visits the Western Wall Tunnels in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019.

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217659.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, visits the Western Wall Tunnels in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019.

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217660.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, visits the Western Wall Tunnels in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019.

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217661.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, visits the Western Wall Tunnels in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019.

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217662.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, touches the stones of the Western Wall in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019, as he campaigns ahead of the parliamentary polls scheduled for April 9.

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217663.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, visits the Western Wall Tunnels in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019.

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217664.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, visits the Western Wall Tunnels in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019.

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217665.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, shakes hands with a supporter at the Western Wall in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019, as he campaigns ahead of the parliamentary polls scheduled for April 9.

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217666.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, visits the Western Wall Tunnels in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019.

BENNY GANTZ campaigning in Israel

Michael Bunel / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0217667.jpg

Retired Israeli general Benny Gantz, one of the leaders of the Blue and White (Kahol Lavan) political alliance, visits the Western Wall Tunnels in Jerusalem's Old City on March 28, 2019.

Illustration Jerusalem

Adrien Vautier / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0180123.jpg

A Jewish believer of African descent makes a prayer at the Wailing Wall.

Illustration Jerusalem

Adrien Vautier / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0180124.jpg

Jewish believers prepare to celebrate the start of the Shabbat at the Wailing Wall.

Illustration Jerusalem

Adrien Vautier / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0180074.jpg

A priest walking at night in the old city of Jerusalem

Illustration Jerusalem

Adrien Vautier / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0180075.jpg

Young Jew reading the Torah in front of the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem.

Illustration Jerusalem

Adrien Vautier / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0180076.jpg

Jewish prayer in front of the Wailing Wall.

Illustration Jerusalem

Adrien Vautier / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0180078.jpg

Young Jew praying on the tomb of King David.

Illustration Jerusalem

Adrien Vautier / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0180079.jpg

No one lighting candles in the Dormition Abbey. It is here that the Virgin Mary could have died.

Illustration Jerusalem

Adrien Vautier / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0180080.jpg

Tourist returning from the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem.

Illustration Jerusalem

Adrien Vautier / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0180081.jpg

Wailing Wall in Jerusalem.

Illustration Jerusalem

Adrien Vautier / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0180082.jpg

Jews praying at the Wailing Wall.

Illustration Jerusalem

Adrien Vautier / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0180083.jpg

Alley in the old city of Jerusalem.

Original Christian holy place of the cave of the Seven Sleepers

Manoël Pénicaud / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0169801.jpg

Known in Islam as the People of the Cave

(Ahl al-Kahf in Arabic), the Seven Sleepers are said to have miraculously slept for several centuries in a cave in order to escape from the persecutions of the Roman Empire. Their awakening is a metaphor for the resurrection

of the body, in both Christianity and in Islam

(Qur’anic sura ‘The Cave’). The narratives

of the Seven Sleepers were widely disseminated. Numerous caves in the Mediterranean region are considered to be sacred places where this miracle occurred. This legend has sometimes given rise to joint veneration by Christians and Muslims.

Crypt of the Seven Sleepers in Ephesus

Manoël Pénicaud / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0169802.jpg

Known in Islam as the People of the Cave

(Ahl al-Kahf in Arabic), the Seven Sleepers are said to have miraculously slept for several centuries in a cave in order to escape from the persecutions of the Roman Empire. Their awakening is a metaphor for the resurrection

of the body, in both Christianity and in Islam

(Qur’anic sura ‘The Cave’). The narratives

of the Seven Sleepers were widely disseminated. Numerous caves in the Mediterranean region are considered to be sacred places where this miracle occurred. This legend has sometimes given rise to joint veneration by Christians and Muslims.

Citadel of Saint John, from the 7 Dormants site, with a wishing tree

Manoël Pénicaud / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0169803.jpg

Known in Islam as the People of the Cave

(Ahl al-Kahf in Arabic), the Seven Sleepers are said to have miraculously slept for several centuries in a cave in order to escape from the persecutions of the Roman Empire. Their awakening is a metaphor for the resurrection

of the body, in both Christianity and in Islam

(Qur’anic sura ‘The Cave’). The narratives

of the Seven Sleepers were widely disseminated. Numerous caves in the Mediterranean region are considered to be sacred places where this miracle occurred. This legend has sometimes given rise to joint veneration by Christians and Muslims.

Sanctuary of the 7 Sleepers in Tarsus

Manoël Pénicaud / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0169804.jpg

Known in Islam as the People of the Cave

(Ahl al-Kahf in Arabic), the Seven Sleepers are said to have miraculously slept for several centuries in a cave in order to escape from the persecutions of the Roman Empire. Their awakening is a metaphor for the resurrection

of the body, in both Christianity and in Islam

(Qur’anic sura ‘The Cave’). The narratives

of the Seven Sleepers were widely disseminated. Numerous caves in the Mediterranean region are considered to be sacred places where this miracle occurred. This legend has sometimes given rise to joint veneration by Christians and Muslims.

The guardian and the imam of the sanctuary. The second recognizes the Christian past in the history of the Seven Sleepers.

Manoël Pénicaud / Le Pictorium

LePictorium_0169805.jpg

Known in Islam as the People of the Cave

(Ahl al-Kahf in Arabic), the Seven Sleepers are said to have miraculously slept for several centuries in a cave in order to escape from the persecutions of the Roman Empire. Their awakening is a metaphor for the resurrection

of the body, in both Christianity and in Islam

(Qur’anic sura ‘The Cave’). The narratives

of the Seven Sleepers were widely disseminated. Numerous caves in the Mediterranean region are considered to be sacred places where this miracle occurred. This legend has sometimes given rise to joint veneration by Christians and Muslims.

Next page